The evolution of quality standards in clinical laboratories has been marked by few requirements for accuracy before the enactment of CLIA’67, voluntary PT programs in the early 1950s that improved laboratory testing, and federal regulations from 1967 to 1988 that aimed to enhance the quality of laboratory tests in federally funded healthcare programs without imposing absolute performance standards.

The CLIA ’88 law was introduced due to the inadequate regulation of cytology, which led to a high rate of false negative results. Unethical practices, such as paying cytotechnologists per slide, taking slides home, and meeting daily quotas, were widespread. Many independent laboratories employed qualified technologists and reported a few unsatisfactory results. Primary care physicians also lacked proper training in sample collection and often provided insufficient clinical information. The CDC held meetings in 1988 to gather information on quality assurance issues in clinical cytology, and The Bethesda System was developed as a result. The Clinical Laboratory Amendments of 1988 extended regulatory processes to physicians’ office laboratories, requiring stringent proficiency testing and quality assurance standards. Proposed regulations were revised in 1992 after objections, defining quality assurance standards for cytology in the US.

QA Plan Requirements and Benefits in Cytology Laboratories

The CLIA ’88 law proposed standards for cytology, and the final rule published in 1992 defined and added more standards, such as workload and pathologist sign-out. The workload limit of 100 slides per 24-hour period was controversial, and the government’s main goal was to prevent abuses. Performance evaluation was the most challenging aspect for laboratories.

CLIA ’88 regulations mandate that all cytology laboratories in the US have a QA plan that satisfies the requirements and is shown to Health Care Financing Administration surveyors to ensure public safety. Even laboratories that are part of a professional society program or located in an exempt state must meet equivalent standards.

Cytology PT (Precision Test) and CLIA ’88

Cytology PT was the most controversial requirement of CLIA ’88 and refers to an annual examination of each individual involved in gynecologic cytology. The standards detail the format and grading system to be used, and penalties result if an unsatisfactory slide is misdiagnosed. The implementation of cytology PT was postponed for two years due to the lack of approved programs.

CLIA ’88 Requirements and Responsibilities for Cytology Laboratory Supervisors and Directors

Under CLIA ’88, technical supervisors in cytology must have specific qualifications and are required to establish workload limits for cytotechnologists. The general supervisor is responsible for overseeing daily laboratory operations, while the laboratory director must ensure proper patient preparation, specimen collection and transportation, and report generation, transmission, and utilization. CLIA ’88’s Subpart J on Patient Test Management introduces quality assurance (QA) concepts that extend the laboratory’s responsibilities to the preferably analytic and post-analytic phases of testing. The laboratory director has the power to develop QA systems that cover all aspects of testing and personnel assessment but also carries the responsibility to ensure proper systems are in place and all phases of laboratory operation are documented.

Quality Control Measures in a Cytology Laboratory

This laboratory has quality control monitors for rescreening negative gynecology cases and detecting two-step discrepancies. The senior cytotechnologist and supervisor review a random sample of 10% of negative cases and high-risk negatives. Discrepancies are forwarded to the pathologist for sign-out. Standards are in place for rescreening and discrepancy rates. The laboratory monitors its quality control program daily and quarterly. Follow-up information from clinics and hospitals is used for cytology/tissue correlation, and overall abnormal and unsatisfactory GYN rates are also monitored.

Quality Assurance in Patient Test Management and Communication

The laboratory has monitors to evaluate patient test management, communications problems, and complaint investigations. Turnaround time is monitored weekly using computer histograms, and the department maintains a high level of accuracy and clarity in its reports to prevent discrepancies. Customer complaints are promptly addressed and corrected, and any questions or issues with specimen collection instructions are communicated to the clinician. The laboratory aims to maintain high levels of quality assurance in these areas.

QA Plan for Cytology Department: Monitoring and Addressing Quality Issues

The QA plan in a cytology department aims to identify and address problems that affect the quality of operations. QA monitors are reviewed regularly and responsibilities for performing and reviewing them may be shared among different personnel. The plan is reviewed weekly by department managers and supervisors, and topics discussed may be brought up in departmental meetings. There are also quality teams within the department that provide reports and feedback. Additionally, the QA plan is reviewed twice a year by the State Laboratory of Hygiene laboratory-wide QA committee. The QA plan is based on 28 monitors grouped under five major headings.

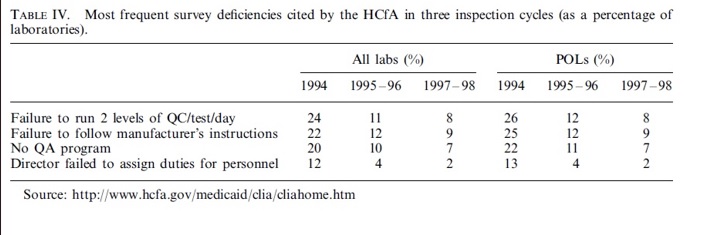

CLIA Regulations in Improving the Quality of Clinical Laboratory Testing

After the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1967 (CLIA’67), there were concerns over the ability of newly regulated POLs to pass proficiency testing (PT). However, data from the Wisconsin State PT Survey suggests that laboratories were able to identify problems through PT and take corrective action. Furthermore, passing PT may reflect better methodologies, instrumentation, calibration, personnel training, and technical support. Data also shows that CLIA’s quality practices are being implemented, with a significant number of laboratories achieving zero deficiencies by the end of the second cycle of inspections. The majority of laboratories have implemented minimum quality practices.

Implementing Personalized Metabolomics in Clinical Practice through Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs)

One possible solution for implementing personalized metabolomics in clinical practice is through the use of laboratory-developed tests (LDTs). LDTs are a subset of in vitro diagnostic devices (IVDs) that are widely used in clinical practice and can measure individual or multiple analytes of various types, including omics-based LDTs for the diagnosis of genetic disorders, cancer, and infections. Although metabolomics-based LDTs are not currently in use, some have been developed by Metabolon, which can measure up to 1,000 metabolites in blood plasma. These tests can be regulated by the protocols and standardization acts of individual laboratories and local rules for diagnostic devices only, and can potentially be performed at a low and acceptable cost. These LDTs were not FDA-approved but were used in CLIA-certified laboratories as auxiliary tests in combination with standard clinical diagnostic tests.

The ultimate goal in laboratory medicine is to ensure the safety and effectiveness of clinical tests and procedures for patients. Both FDA-approved kits and laboratory-developed procedures performed under CLIA have their place in achieving this goal. On-site testing is important to integrate results with other clinical and laboratory findings, interpret them as a whole, and provide timely results. It is also important to provide hands-on training to the next generation of physicians to ensure they can effectively utilize genomic and other laboratory information in their practice. The promise of personalized medicine can be realized through these efforts.

The Goal of Laboratory Medicine in Achieving Personalized Medicine

The ultimate goal in laboratory medicine is to ensure the safety and effectiveness of clinical tests and procedures for patients. Both FDA-approved kits and laboratory-developed procedures performed under CLIA have their place in achieving this goal. On-site testing is important to integrate results with other clinical and laboratory findings, interpret them as a whole, and provide timely results. It is also important to provide hands-on training to the next generation of physicians to ensure they can effectively utilize genomic and other laboratory information in their practice.

Future Implications of CLIA in Clinical Labs

As laboratory medicine advances, CLIA regulations and guidelines must evolve to ensure the safety and efficacy of laboratory tests and procedures. Future implications include updating and expanding regulations and guidelines to keep up with advancements in technology and practices. One potential implication is incorporating more genomic testing into clinical practice, addressing issues related to the accuracy, reliability, and ethical considerations. Increased standardization and harmonization of laboratory practices and procedures may also be necessary, including the development of consensus practice guidelines and the use of reference materials. Overall, CLIA will need to adapt to meet changing needs while maintaining a focus on patient safety and the effectiveness of laboratory tests and procedures.

The Challenges and Regulations Related to Point-Of-Care Testing

The CLIA regulates all laboratory tests conducted on humans, including point-of-care testing (POCT) which has different regulations based on the difficulty of the test. Advances in POCT connectivity and data management will lead to less manual documentation, and training is crucial for compliance with federal and accreditation organization requirements. Managing reagents, QC, and cleaning/disinfection of devices are important factors in preventing errors and complying with regulations. Lack of agreement between POCT and central laboratory results can confuse and requires staff training. Understanding the limitations of POCT can enhance result reliability.

The Impact of CLIA Regulations on Clinical Laboratory Operations

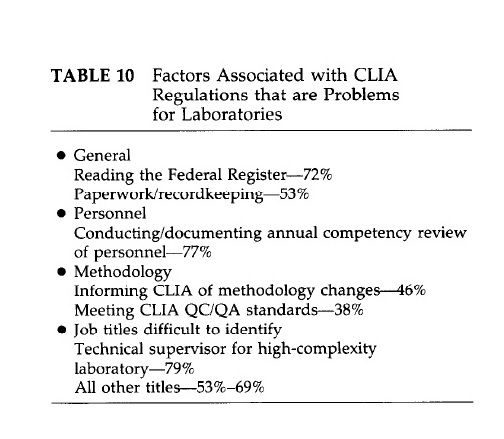

The daily operations of clinical laboratories are significantly affected by the paperwork and documentation required by CLIA regulations. These regulations entail various fees, including certification, inspection, proficiency testing, and yearly payments for microbiology testing. HCFA estimates an increase in testing costs of $0.25 per test. A survey published in the Medical Laboratory Observer and data from HCFA identify several CLIA-related factors that pose significant challenges for laboratories, such as the extensive documentation required for mandated quality assurance and quality control activities and issues with proficiency testing. The major difficulty areas are summarized in the figure below.

References

- Bogdanich W. Lax laboratories: “The Pap test misses much cervical cancer through labs’ errors”, Wall Street J, Nov 1987.

- Department of Health and Human Services, 42 CFR Parts 405 Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, Final Rule. Fed Reg 1992; 57 (February 28):700 1-7288.

- S. S. EHRMEYER & R. H. LAESSIG,” Effect of legislation (CLIA’88) on setting quality specifications”, Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1999; 59: 563 – 568.

- Zehnbauer B, Lofton-Day C, et.al,” Diagnostic quality assurance pilot: a model to demonstrate comparative laboratory test performance with an oncology companion device assay”, J Mol Diagn. 2017; 19: 1-3. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.10.001.

- Joesph Wiencek & James Nichols (2016): “Issues in the practical implementation of POCT: overcoming challenges”, Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics, DOI: 10.1586/14737159.2016.1141678.

- Jahn M (1992), “The shortage gets worse, but laboratorians get better”, Medical Laboratory Observer Sept.:2&29.

- Jahn M (1994a),” CLIA after year 1: no help to patients, and a hindrance to labs”, Medical Laboratory Observer May: 20-26.