MS is an autoimmune condition of the CNS that is chronic and has significant social and economic consequences. MS affects millions of people worldwide and is also a leading cause of neurological disability in young adults. The highest prevalence was noted in North America, Western Europe, and Australasia.

MS was first described by a prominent French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot in the 1860s. Over the next century, hundreds of treatments for this perplexing disease were suggested, many of which were unconventional.

MS is an immunological and most likely autoimmune disease that is impacted by both environmental and genetic factors.

Understanding the Subtypes of Multiple Sclerosis and Current Treatment Options

The four main subtypes of multiple sclerosis (MS) are; clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS), and primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS). SPMS can be further divided into active and non-active categories. CIS is the term used for the first episode of neurologic symptoms, which usually lasts at least 24 hours. Relapse refers to new neurologic symptoms that last for 24 to 48 hours and stem from a new injury in the brain. RRMS is the most common and generally mild subtype of MS. In PPMS, there are no early relapses or remissions, but neurologic function declines from the onset of MS symptoms. Treatment strategy for MS depends on the subtype, so correctly distinguishing between the different subtypes is important.

Current treatment options for MS are focused on reducing inflammation, preventing or delaying relapses, and slowing the disease progression. The most common medications are disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), which are taken orally or by injection. They can reduce inflammation and prevent the immune system from attacking the myelin sheath. Also, presently, only ocrelizumab and occasionally mitoxantrone are sanctioned for primary progressive MS. Mitoxantrone, however, has dose-dependent cardiac toxicity and requires echocardiography monitoring. β-Interferons and glatiramer acetate are administered via subcutaneous injection and are known for their excellent safety profiles, making them the longest-used approved MS treatments, known as platform therapies. Teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate are oral medications that some patients prefer. While they offer similar or slightly superior efficacy to interferons or glatiramer acetate, they carry some risks.

Antibody-based Precision Medicine as a Promising Alternative for Multiple Sclerosis

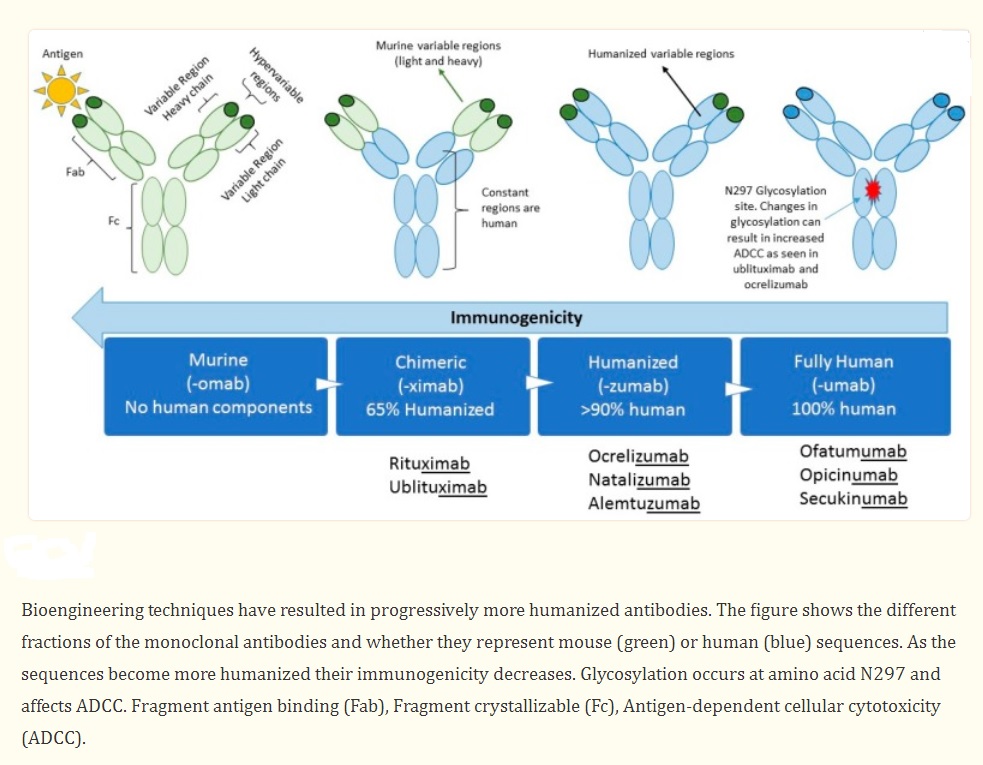

The current objective of immunomodulatory treatments is to decrease the frequency and severity of clinical exacerbations and to stop the disease progression. Biologics, which are proteins designed or optimized using genetic and protein engineering, show great potential as a treatment option. Among these, therapeutic monoclonal antibodies are highly versatile. Initially, mAb treatment aimed to eliminate certain immune cell subsets believed to be pathogenic. However, recent research has shown that non-depleting mAbs can have subtle immunoregulatory effects and might even induce lasting immune tolerance.

Even though MABs have shown great efficacy in treating MS, concerns about side effects persist among some healthcare providers and patients. Unpredictable immune reactions such as serum sickness and anaphylaxis can be minimized by humanizing MABs. Factors to consider when switching a patient to or from MAB therapies include evidence of disease activity, side effects, ease of administration, and costs. Comprehensive knowledge of the action mechanism, techniques for monitoring negative effects, and tactics for evaluating the effectiveness of treatments are not only fundamental components of personalized medicine, but are crucial for ensuring the safest possible care for MS patients.

Advances in the Use of MAbs and the Treatment of MS

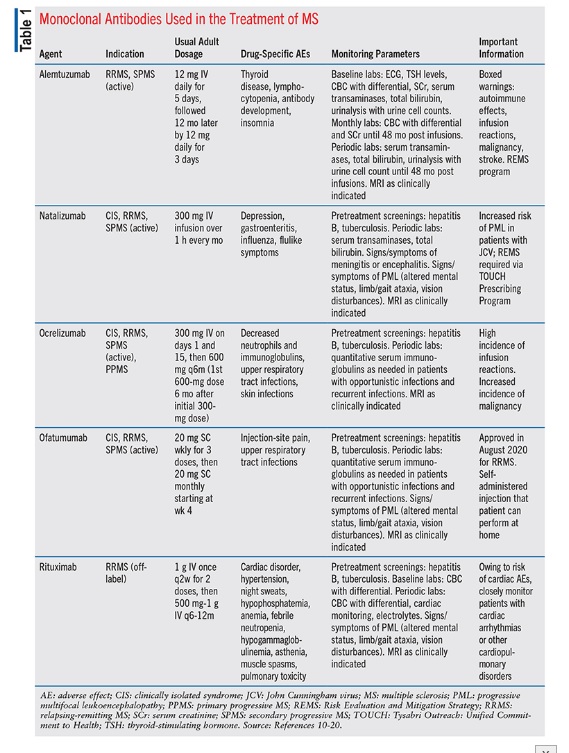

The last two decades have been significant in the development of treatment for relapse-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), which can potentially stabilize disease activity and even improve function in some patients. Evidence shows that there is an early therapeutic window for MAbs to be effective. While MAbs are more effective than injectable treatments, they also have more serious side effects that must be balanced with their benefits. They are more convenient for patients since they require less frequent administration. The cost of these treatments may be an important factor in countries where healthcare budgets are under pressure. Below are the MAbs that are currently used for treating MS or will soon be approved by regulatory agencies.

Natalizumab : It was the first MAB to receive FDA approval in 2004 as a treatment for MS. However, due to cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), it was temporarily taken off the market. After the development of a monitoring program for PML cases, it was returned to the US market in 2006. Natalizumab has been highly effective in treating MS patients. According to the AFFIRM study, natalizumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 68% compared to placebo after one year.

Ocrelizumab: This is a humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically targets CD20. The FDA granted approval for ocrelizumab in 2017 for relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and primary progressive MS (PPMS). This treatment is administered via intravenous infusion every six months. In clinical trials, ocrelizumab has shown a significant decrease in the number of new or growing brain lesions and has delayed the onset of confirmed disability progression. In patients with RRMS, ocrelizumab was found to lower the annualized relapse rate by 46% in comparison to a placebo. For patients with PPMS, the medication was shown to reduce the risk of confirmed disability progression by 24% when compared to a placebo.

Rituximab: It is a type of chimeric MAB that binds to CD20, causing B cells to be destroyed through complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). Although not approved by FDA for MS treatment, rituximab has been commonly used off-label in clinical practice and is highly effective in treating relapsing MS. The HERMES phase II study revealed that patients receiving rituximab had a substantial decrease in the total number of contrast-enhancing lesions over a 24-week period when compared to those receiving a placebo. In addition, studies have indicated that rituximab may also be effective in reducing relapses and delaying the progression of disability in individuals with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and primary progressive MS (PPMS).

Ofatumumab: This is presently undergoing phase 3 clinical trials for the treatment of relapsing MS. In a previous small-scale phase II study, it was discovered that all dose groups of ofatumumab resulted in a 99% reduction in new MRI lesions compared to the placebo after 24 weeks. The MIRROR study, a phase IIB trial that utilized subcutaneous dosing and compared ofatumumab to placebo, showed that all dose groups had a 65% reduction in cumulative new gadolinium lesions when compared to placebo. Ofatumumab is available in several countries worldwide for treating relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS) and can be self-administered by patients.

Ublituximab: It is currently undergoing phase III studies (ULTIMATE). In clinical trials, it has been demonstrated that ublituximab significantly decreases the number of new or enlarged brain lesions and reduces the likelihood of relapse when compared to a placebo. Moreover, after 24 weeks, almost all participants (98%) did not experience relapse, no subjects exhibited a contrast-enhancing lesion, 84% did not have any new or enlarged T2 lesion, and 93% did not have confirmed disability progression, leading to 76% of subjects satisfying the criteria for having no evidence of disease activity.

Alemtuzumab: As a humanized monoclonal antibody treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), was approved for licensing by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in September 2013, followed by approvals from regulatory authorities in other countries. The drug targets the surface of lymphocytes and monocytes. While B cells repopulate within six weeks of treatment, T cells take longer to normalize, with a timeframe of 9-12 months after the treatment course. This provides a long-lasting pharmacodynamic effect, which enables the drug to be administered intravenously over two treatment courses.

Opicinumab: This is an investigational drug for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) by targeting the LINGO-1 protein. LINGO-1 is crucial for the growth and differentiation of oligodendrocytes, which produce the myelin sheath. During the RENEW phase II trial, Opicinumab was assessed as an additional treatment for individuals suffering from optic neuritis. However, by the 24th week, no notable distinction in remyelination rates between the group that received Opicinumab and the placebo group.

When is switching to a Monoclonal Antibody considered the best option for controlling disease activity?

The initial treatment for most patients with mildly to moderately active MS involves first-line therapies, which are safe and have long-term safety data available. If the disease breaks through, patients may be switched to a stronger treatment. However, there is no available data for a direct comparison of efficacy among second-line drugs. Therefore, the choice of therapy must be based on the patient’s risk profile and clinical condition. Although some argue that second-line drugs should be used as first-line treatments due to their enhanced efficacy, this must be balanced against the potential risks. Studies suggest that switching to a monoclonal antibody may be the best option when a disease breakthrough occurs with first-line therapy to control disease activity.

References

- Hohlfeld, Reinhard; Wekerle, Hartmut (2005). Drug Insight: using monoclonal antibodies to treat multiple sclerosis. Nature Clinical Practice Neurology, 1(1), 34–44. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0016

- Voge NV, Alvarez E. Monoclonal Antibodies in Multiple Sclerosis: Present and Future. Biomedicines. 2019 Mar 14;7(1):20. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines7010020. PMID: 30875812; PMCID: PMC6466331.

- https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/current-monoclonal-antibody-options-for-multiple-sclerosis

- Kang C, Blair HA. Ofatumumab: A Review in Relapsing Forms of Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs. 2022 Jan;82(1):55-62. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01650-7. Erratum in: Drugs. 2021 Dec 29;: PMID: 34897575; PMCID: PMC8748350.

- Havrdova E, Horakova D, Kovarova I. Alemtuzumab in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: key clinical trial results and considerations for use. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2015 Jan;8(1):31-45. doi: 10.1177/1756285614563522. PMID: 25584072; PMCID: PMC4286943.

- https://doi.org/10.17925/ENR.2018.13.2.78