The practice of medicine has always focused on the individual patient and providing the best treatment for their specific needs. Precision medicine, which aims to provide the right therapy for the right patient at the right time, is not a new concept. However, recent advances in our ability to assess genetic and metabolic variation, use data to inform disease categories, and make science-guided treatment decisions have greatly improved our ability to personalize medicine. This is particularly relevant in the case of diabetes, where hyperglycemia is the hallmark of the disease but can have many underlying causes. Type 1 diabetes is caused by the autoimmune destruction of beta-cells in the pancreas, whereas type 2 diabetes involves multiple physiological pathways. Other forms of diabetes can be caused by a variety of factors, including genetics and other medical conditions. With the help of digital devices, electronic medical records, and lifestyle/environmental data, precision medicine holds great promise for optimizing diabetes treatment.

Advancements in Technology and Biology: Improving Diabetes Treatment and Management

The advancement in technology and understanding of biology has allowed doctors and researchers to study individuals comprehensively, which helps them infer general principles to select an appropriate treatment plan. However, incorporating these insights into medical decision-making requires careful evaluation and translational strategies that involve specialist training, education, and policy considerations. Diabetes is a complex disease that requires targeted therapies and biomarkers to facilitate immune intervention trials and aid in the detection of environmental triggers. With multiple biomarkers and genetic variants, doctors can alter the risk of type 2 diabetes, which provides new therapeutic targets. Moreover, with the tools and resources available today, doctors can determine the biological and lifestyle/environmental predictors of drug response, allowing them to make informed decisions about treatment options for patients.

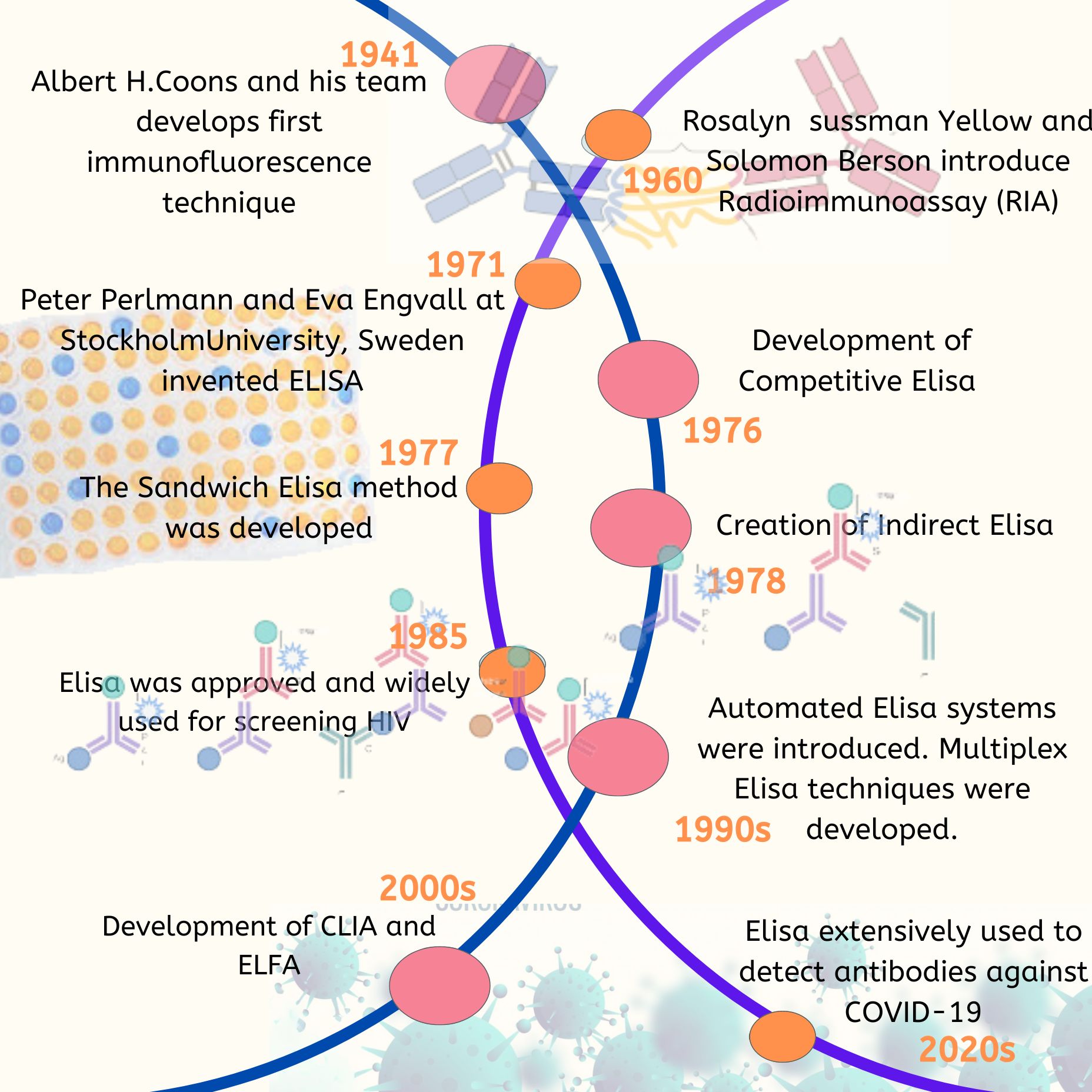

Precision Medicine in Diabetes Initiative (PMDI)

The Precision Medicine in Diabetes Initiative (PMDI), launched in 2018 by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), aims to reduce the burden of diabetes worldwide through the implementation of precision medicine. The PMDI is working to establish consensus on the viability and potential of precision medicine for the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of diabetes by evaluating available evidence and engaging with stakeholders. The initiative is focused on promoting research, providing education, and developing guidelines for precision medicine in diabetes. Symposia and postgraduate education programs will be used to translate science into practice, and a global clinical research network will be established. The objective is to improve the lives of people with diabetes and promote longer, healthier futures for them.

Components and Objectives of precision diabetes medicine

Precision diabetes medicine is a method that aims to improve the diagnosis, prediction, prevention, and treatment of diabetes through the integration of multidimensional data that takes into account individual differences. Unlike standard medical approaches, this method uses complex data to determine an individual’s health status, predisposition, prognosis, and potential response to treatment. It also focuses on identifying patients who may not require treatment or need less treatment than usual. Data sources can include clinical records, “big data” like medical records and behavioral monitors, sensors, and genomic data. Patient preferences, cost-effectiveness, patient-centered outcomes, and shared decision-making will guide the use of precision diabetes medicine.

Precision therapy and prevention in diabetes

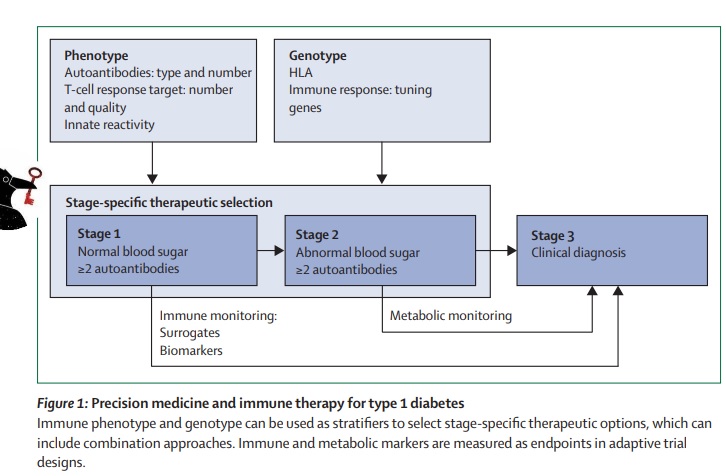

Precision therapy requires accurate diagnosis for successful prevention or treatment of diabetes. This is particularly important when defining subgroups of the population that will receive targeted interventions, as well as determining treatment outcomes. In monogenic diabetes, prevention options are not currently known, while in type 1 diabetes (T1D), precision prevention primarily involves optimizing monitoring methods to allow for early detection and appropriate treatment. On the other hand, type 2 diabetes (T2D) has many avenues for prevention, with possibilities for precision approaches such as tailoring lifestyle choices like diet. T1D progression occurs in discrete stages, and a clinical diagnosis is typically not given until stage 3 when symptoms of dysglycemia are present. Genetic factors, particularly genes of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex and over 50 non-HLA loci account for approximately half the risk of T1D, with environmental factors thought to trigger the autoimmune process that leads to initial b-cell damage and progression towards symptomatic T1D.

The natural history of Type 1 Diabetes and the potential for antigen-based immunotherapy

Studies on natural history, incorporating thousands of individuals at risk of type 1 diabetes, have shown that the disease process usually begins early in life and progresses through well-defined stages of immune and metabolic abnormalities before clinical symptoms arise. Loss of immunological tolerance is observed at all stages of type 1 diabetes development, including the presence of autoantibodies against multiple targets and CD4 and CD8 T cells recognizing the same autoantigens. This immune dysfunction is tissue-restricted and HLA-dependent and is the major immunopathological feature of the disease. With the emergence of screening programs, patients are increasingly presenting with intact C-peptide production, drawing attention to the tolerance issue and the potential use of antigen-based immunotherapy.

Antibody therapies for type 1 diabetes in murine models

In 1990, the Cohen group discovered that an autoantigen called hsp65, which is cross-reactive with Mycobacterium tuberculosis is involved in the development of type 1 diabetes in NOD/Lt mice. They found that vaccination with the hsp65 protein protected against diabetes. They also identified a T cell epitope called p277, which contains amino acid residues 437-460 of the hsp60 protein. Subsequent studies showed that p277 could prevent diabetes when administered to prediabetic NOD mice, but later studies produced contradictory results. The only antibody therapies that have successfully cured early diabetes in murine models are polyclonal anti-lymphocyte 3.2.2 peptide p277 cyte antisera (ALS), anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies, and anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies. These therapies work by inducing transient lymphodepletion, which lasts for a few days to a few weeks, to suppress autoimmune T cells and restore normal blood sugar levels. While ALS and anti-CD4 antibodies act primarily as immune suppressors, anti-CD3 antibodies are considered immune modulators and are highly promising as a therapy for type 1 diabetes.

Anti-CD3 Antibody Therapy for Type 1 Diabetes: History, Challenges, and Promising Results

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that causes insulin deficiency, and patients have relied on insulin injections for almost 100 years. Despite numerous clinical trials and research, there is currently no cure or preventative treatment for T1D. However, a recent prevention trial using the anti-CD3 antibody teplizumab has shown promising results in delaying the onset of T1D in high-risk individuals. The use of anti-CD3 in T1D treatment has a complicated history, and while its molecular actions on T lymphocytes are well-understood, its overall effect on the immune system has been difficult to determine. Early preclinical data suggested limited utility for anti-CD3 in preventing T1D, but the latest clinical data is encouraging and shows how a basic discovery can become a promising therapeutic candidate with perseverance and time.

Mechanisms of Anti-CD3 Therapy-Induced Immune Tolerance

In the early stage of anti-CD3 therapy, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are activated and express CD69. In vitro, studies have shown that anti-CD3 therapy triggers activation-induced cell death (AICD) in activated T cells, which may explain its ability to induce immune tolerance. However, the in vivo data is controversial. While some studies have shown that anti-CD3 therapy can induce T cell apoptosis in vivo, others have suggested that it induces unresponsiveness to stimuli of mitogens without inducing T cell death. Therefore, anti-CD3 therapy likely involves mechanisms beyond T cell depletion, and other tolerogenic mechanisms may be involved.

Role of IL-1β in the development of type 2 diabetes

Recent studies have shown that IL-1β is a primary agonist in the loss of beta-cell mass in type 2 diabetes. In vitro, studies have shown that IL-1β-mediated autoinflammatory processes lead to beta-cell death, which is driven by glucose, free fatty acids, leptin, and IL-1β itself. Caspase-1 is required for IL-1β activity and the release of free fatty acids from adipocytes. An imbalance between the amount of IL-1β agonist activity and the counteracting effect of the naturally occurring IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) can determine the outcome of islet inflammation. Clinical trials using anakinra, the recombinant form of IL-1Ra, or neutralizing anti-IL-1β antibodies have shown that reducing IL-1β activity is sufficient for correcting dysfunctional beta-cell production of insulin in type 2 diabetes, with the possibility that suppression of IL-1β-mediated inflammation in the islet’s microenvironment allows for regeneration.

Anti-CD20 antibody therapy in type 1 diabetes

B cells are a type of immune cell that produce antibodies in response to foreign or self-antigens. Self-reactive B cells have been linked to autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and idiopathic thrombocytopenia, and their depletion has been shown to improve these conditions. The B cell-specific marker CD20 is highly expressed in mature B cells, making it a target for in vivo depletion using anti-CD20 antibody therapy. Rituximab, an FDA-approved drug targeting CD20+ B cell lymphoma, has been used successfully for over a decade. Recent clinical trials have shown promising results using anti-CD20 therapy for B cell-mediated autoimmune diseases, including new-onset type 1 diabetes. However, the efficacy and potential side effects of this treatment need to be further explored, along with potential solutions to existing issues.

The potential of Rituximab as a treatment for new-onset type 1 diabetes

In 2009, a clinical study by the T1D TrialNet Anti-CD20 study group investigated the effect of Rituximab on new-onset type 1 diabetes in 87 patients. Results showed that the Rituximab group had higher mean C-peptide levels, reduced glycated hemoglobin and insulin requirements, and minimal adverse events. The study suggested that anti-CD20 therapy is a promising approach for treating type 1 diabetes, but further investigation is needed to determine the need for repeat therapy and long-term protection.

Opportunities for improving precision medicine for diabetes with antibodies

Precision medicine aims to provide personalized and targeted therapies based on an individual’s unique genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Antibodies have emerged as promising targets for precision medicine in diabetes. Here are some opportunities for improving precision medicine for diabetes with antibodies:

Developing antibodies that target specific pathways: Diabetes is a complex disease with multiple pathways involved in its development and progression. By developing antibodies that target specific pathways, it may be possible to achieve better outcomes by targeting the underlying causes of the disease.

Biomarker-guided treatment: Antibodies can be used to target specific biomarkers associated with diabetes. By identifying biomarkers that are associated with specific subtypes of diabetes, it may be possible to develop targeted therapies that are more effective and have fewer side effects.

Combination therapies: Diabetes is a complex disease, and it may be necessary to use a combination of therapies to achieve optimal outcomes. Antibodies can be used in combination with other drugs or therapies to provide a more comprehensive treatment approach.

Personalized dosing: Antibodies can be dosed according to an individual’s unique characteristics, including weight, age, and kidney function. This personalized dosing approach can help to optimize drug efficacy while minimizing the risk of adverse events.

Monitoring response: Antibodies can be used to monitor treatment response in real time. By monitoring biomarkers and other indicators of disease progression, it may be possible to adjust treatment regimens and improve outcomes.

References

- Wendy K. Chung, Karel Erion, Jose C. Florez, Andrew T. Hattersley, Marie-France Hivert, Christine G. Lee, Mark I. McCarthy, John J. Nolan, Jill M. Norris, Ewan R. Pearson, Louis Philipson, Allison T. McElvaine, William T. Cefalu, Stephen S. Rich, Paul W. Franks; Precision Medicine in Diabetes: A Consensus Report From the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 1 July 2020; 43 (7): 1617–1635. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci20-0022.

- Bart O Roep, Daniel C S Wheeler, Mark Peakman, “Antigen-based immune modulation therapy for type 1 diabetes: the era of precision medicine”, The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, Volume 7, Issue 1,2019, Pages 65-74, ISSN 2213-8587,https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30109-8.

- Ben-Amor A, Leite-De-Moraes MC, Lepault F, Schneider E, Machavoine F, Arnould A, Chatenoud L, Dy M: In vitro, T cell unresponsiveness following low-dose injection of anti-CD3 MoAb. Clin Exp Immunol 1996, 103(3):491-498.

- irgolini L, Marzocchi V: Rituximab in autoimmune diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2004, 58(5):299-309.

- Xia, C.-Q., Liu, Y., Guan, Q., & Clare- Salzler, M. J. (2013). Antibody-Based and Cellular Therapies of Type 1 Diabetes. InTech. doi 10.5772/53495.

- Evans-Molina, C., & Oram, R. A. (2023). Teplizumab approval for type 1 diabetes in the USA. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.